Academic innovation offices are critical stewards of our collective public investment in research and development. Innovations conceived in academia can have tremendous societal benefit when they are translated into the private sector.

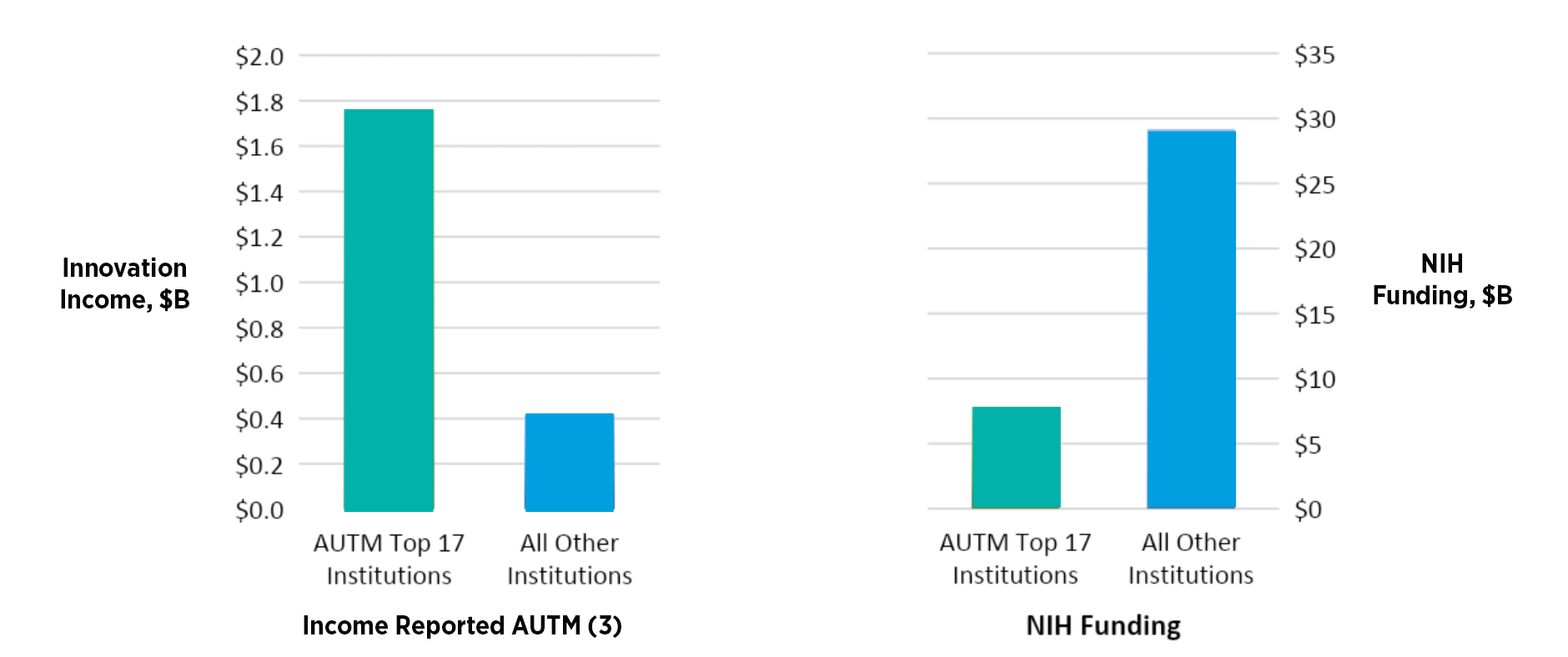

It is well known among academic innovation offices that a handful of academic institutions have immensely productive innovation and commercialization enterprises. For example, a recent AUTM survey (1) found that only 17 of 183 responding institutions reported adjusted gross income exceeding $50M. Collectively, these 17 institutions generated over 4 times the innovation income of all other responding institutions combined.

Unsurprisingly, many of these 17 institutions are located in major innovation hubs like Boston and the San Francisco Bay area. They benefit from proximity to angel investors and venture capital, as well as substantial research enterprises and well-resourced innovation and technology transfer offices.

Interestingly, this concentration of innovation income is very much at odds with how federal funding for research is allocated throughout the country. The vast majority of basic scientific research in the U.S. is supported by federal grants, the largest provider of which is the National Institutes of Health (NIH). According to data published by the Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research (2), the 17 institutions discussed previously collectively receive about one-quarter of the NIH funding which flows to other institutions.

This observation is perhaps counterintuitive, although we note that our calculations are of a back-of-the-envelope nature. Among other issues, a rigorous analysis would encompass multiple years of data and more carefully deal with outliers. For example, a windfall from commercializing a single, high-value drug may dramatically increase an institution’s income for a period of time, but it may not be sustained or representative of their income over time.

Still, this data point speaks to an interesting dynamic and strongly suggests how much we collectively stand to gain in technological and medical advancement if we can help the broad swath of academic institutions commercialize a similar share of their federally funded research as the top performers, narrowing the innovation gap. An institution’s licensing revenue or its number of startups may be imperfect proxy measurements for its impact on technological or medical advancement, but as a society we have an imperative to make our collective investment in research as impactful and beneficial as possible. With most of our investment going outside the hub-based innovation super-producers, finding a way to maximize the commercial success of the broad array of institutions is critically important.

About Odgers Berndtson

For over 50 years, Odgers Berndtson has helped some of the world’s biggest and best organizations find senior talent to drive their agendas. The firm still operates with the agility of a young company through a unique culture that puts values ahead of rules. Odgers Berndtson’s strength lies in the partnerships we develop. We form enduring relationships with the most talented people – candidates, clients, colleagues. There is a relentless drive to ensure a client and candidate experience that is exceptional. This comes from a true culture of collaboration, respect, and humility, recognizing that asking the right questions is more important than knowing the old answers.

We deliver executive search, assessment, and development to businesses and organizations varying in size, structure, and maturity. We do that across over 50 sectors, whether commercial, public, or not-for-profit and draw on the experience of more than 300 Partners and their teams in 29 countries.

(1) AUTM Licensing Activity Survey, https://autm.net/surveys-and-tools/surveys

(2) Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research, https://brimr.org/

(3) Adjusted gross income, or, if not provided, gross license income